Overview

Overview

My research interests: an elevator pitch1

My broad research interest lies in theoretical aspects of computer science. I am specifically interested in understanding the potential and the limitations of computational power. To this end, we use abstractions that model what computers do, as opposed to, say, analyzing a specific configuration or engineering faster hardware. While this approach does not directly advance state of the art computing tech, it does help with understanding what we can and cannot do with the increasing amounts of computing power at our disposal in a tech-agnostic fashion. This means that most lessons will remain relevant even after you’ve upgraded your systems to use the next generation of hardware, and after that too.

Most of my work concerns the design and analysis of algorithms for computational problems. The problems I work with are usually inspired from applications that someone cares about, for example:

- Finding patterns in large networks (e.g, discovering closely-knit communities in friendship networks).

- Determining who should win an election given a set of votes.

- Distributing resources among people (who may value them differently) in a way that makes everyone happy.

- Coming up with strategies to win a game of solo chess.

- Figuring out how to contain the spread of a fire by deploying as few firefighters as possible.

For some of these scenarios, it may not be immediately obvious what the computational problem is. For example, consider the issue of who must win an election: you would like to create a reasonable mechanism to build a consensus from a set of votes. What would be considered reasonable?

Well, you could list out some natural properties that you would want your mechanism to satisfy (for instance, if all voters have the same favorite candidate, it would be very unreasonable for the mechanism to not pick such a candidate as a winner). And then you could seek out a mechanism that satisfies all of these properties. This is the so-called axiomatic approach to voting, and the approach has even led to the discovery of some fascinating impossibility results, indicating that some combinations of properties cannot be achieved by any mechanism, no matter how clever. Now, among other aspects, one would hope that mechanisms we come up with can be efficiently implemented. It turns out that many mechanisms that have a lot of appealing properties are complex to implement, and some of my work involves finding ways of making them more accessible.

While some computational problems admit elegant solutions that have fast implementations in the real world, for several others we have substantial theoretical evidence suggesting that such solutions are going to be elusive. This means that for all practical purposes we have to work our way through trade-offs.

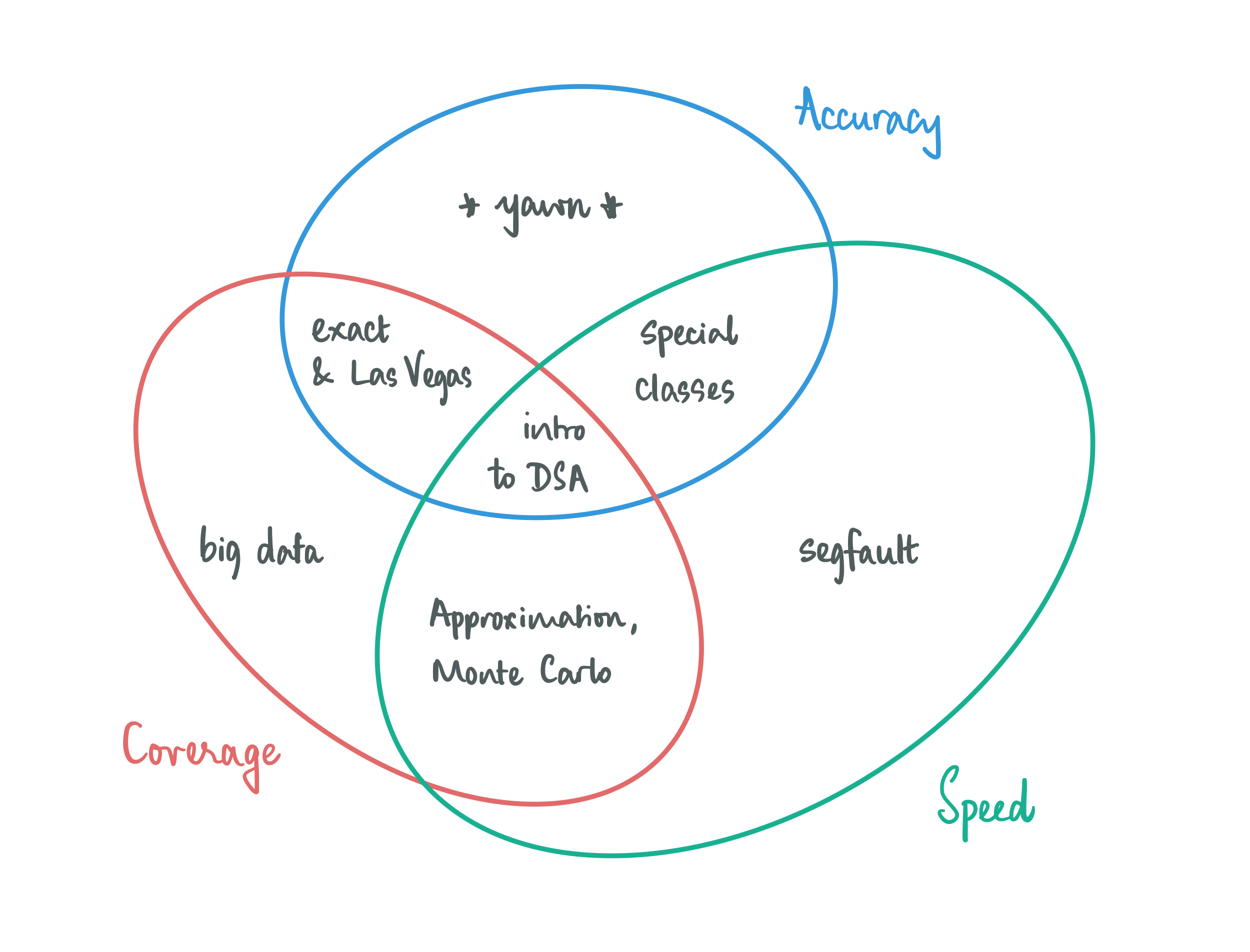

When we think about designing algorithms, we are usually very demanding in how we go about it: we require our algorithms to be fast and accurate on all conceivable inputs. This is asking for quite a bit, and perhaps it is not surprising that we cannot afford this luxury all the time. The good news is that most of the time we can make meaningful progress by relaxing just one of these demands:

Give up on accuracy, but not completely: look for solutions that are good enough (approximation) and/or work with algorithms that report the right solution most of the time (Las-Vegas style randomization).

Give up on coverage, a little bit: let your algorithms work well on structured inputs. Hopefully the structure is such that it is not too limiting and is interesting enough for some application scenario, and is also enough to give you algorithmic leverage, i.e, there’s enough that you can exploit to make fast and accurate algorithms.

Give up on speed, to some extent: going beyond the traditional allowance of polynomial time, which is the holy grail of what is considered efficient, takes you places. You could either allow for your algorithms have super-polynomial running times, and optimize as much as possible while being accurate on all inputs (exact algorithms), or allow for bad running times on a bounded subset of instances (Monte-Carlo style randomization).

One approach that tackles all of these tradeoffs at once is to take what is now called a “multivariate approach” to the analysis of running times, which essentially involves appreciating that to describe a problem instance just in terms of its size is like describing a movie by a rating, which is unfortunate because there’s so much more nuance. And yet we report — and think about — worst-case running times in only terms of the sizes of the instances. Consider, for example, how much more informative it is to think of the running time of BFS as O(n+m) rather than O(n^2), also a valid upper bound2. Notice how the latter fails to convey the fact that the running time of BFS is as good as linear on sparse graphs.

So the parameterized approach takes into account problem structure by addressing “secondary” measurements (parameters), apart from the primary measurement of overall input size, that significantly affect problem computational complexity. The central notion of fixed parameter tractability (FPT) is a generalization of polynomial-time based on confining any non-polynomial complexity costs to a function only of these secondary measurements. For instance, if you have an algorithm for vertex cover whose running time is O(2^{\Delta(G)}) \cdot n^{O(1)}, where \Delta(G) is the maximum degree of the input graph3, then notice that you would have solved vertex cover in polynomial time on all graphs whose maximum degree is, say, O(\log n). Sadly, since we know vertex cover to be NP-complete even when restricted to cubic graphs, this specific goal is a bit of a pipedream, but hopefully you see the potential4 in the process.

To illustrate how useful this approach can be, consider the typechecking problem for ML, a programming language for which relatively efficient compilers exist. One of the problems the compiler must solve is the checking of the compatibility of type declarations. This problem is known to be EXP-complete (Henglein and Mairson 1994): let’s just say intractable in the classical world. However, the implementations work well in practice because the ML Type Checking problem admits an algorithm (Lichtenstein and Pnueli 1985) with a running time of O(2^kn), where n is the size of the program and k is the maximum nesting depth of the type declarations. Since normally k is a small constant5, the algorithm is clearly practical on inputs one would expect to encounter in practice.

Back to why this approach captures algorithmic tradeoffs in the regime of hard problems beautifully. You can think of an algorithm that is FPT in some parameter k as giving you efficient algorithms for that subclass of instances where k is small enough for the algorithm to be efficient. You could also think of it as giving you full coverage but giving up on efficiency as your parameter values loom larger. Finally, you can also devise randomized and/or approximate FPT algorithms, to have the FPT efficiency gains while giving up on accuracy, which may be necessary either for speedups or when working with problems that would not have FPT algorithms otherwise (like we just saw for vertex cover parameterized by maximum degree).

Parameterized (aka multivariate) algorithmics are a wonderfully flexible framework that allows you to dabble in various algorithmic tradeoffs. Once you start thinking in terms of restraining the combinatorial blowups to certain parameters of interest, you’ll probably find that the approach leads you to new ways of looking at the problem! To stay true to the motivations of the field: which is to find ways of “coping with NP-hardness” when said NP-hard problems are ones we need to solve in the real world — one must remember to sanity checck the relevance of the parameters we are working with. An ideal set of parameters would be small for most instances in real-world distributions, but also give you enough flex to devise efficient algorithms.

For a delightful history of the field, I recommend (Bodlaender et al. 2012). Also, (Cygan et al. 2015) is a very accessible introduction to the field, only assuming a background in undergraduate algorithms. The FPT Wiki is a community-maintained resource that documents developments in the field as they happen.

This framework has been my default way of thinking about algorithms for a while now. In the following, I delve a little further into the specifics of the kinds of problems I have been working on.

Games on graphs ⸱ Voting ⸱ Fair Division ⸱ Combinatorial Games ⸱ Backdoors to SAT ⸱ Eliminating Forbidden Subgraphs

Incidentally, I am also interested in issues of CS education, mostly from the perspective of a poorly performing practitioner.

References

Footnotes

for a suitably long elevator ride — assume skyscraper.↩︎

Here, I am using n and m to denote the number of vertices and edges in the input graph G.↩︎

Once again, n denotes the number of vertices in the input graph G.↩︎

It would remiss to not point out that several algorithms for vertex cover turn out to be efficient from the parameterized perspective and useful in practice!↩︎

indeed, if k is not a small constant, you probably have bigger problems anyway↩︎